I am my father’s daughter. From the age of three, I accompanied him to BC Children’s Hospital, where he worked as a pediatric oncologist. The hospital’s emergency room, call rooms and doctors were regular fixtures in my childhood.

To those who knew me, it was not surprising that I would follow in my father’s footsteps. I was inspired by his love of medicine, but perhaps even more, he and my mother’s strong belief in and dedication to community service and social responsibility. For as long as I can remember, my parents would make regular trips to China to provide medical care and education in developing cities, rural towns and minority villages. I chose to study medicine in Hong Kong so I could more easily pursue such opportunities. Be it battling altitude sickness on our way to see patients near Tibet, or hiking hours to a clinic site only to be greeted by hundreds of villagers who had travelled even longer distances to see us, I loved meeting the challenge of these tests of faith in attempts to reach the unreached.

In my third year of my pediatrics residency, though, something changed. The growing identity of “Dr.” grew heavy on my shoulders. Whether it was coping with the increasing demands of training or adjusting to the reality I would soon be an attending physician, I felt my roles and responsibilities as a burden, and I attempted to escape. In an act of rebellion, I went on a non-medical service trip to Rwanda to do everything but see patients. I cleaned washrooms, visited street kids, and even worked in a village to make mud bricks for a cowshed.

One day while visiting the Genocide Memorial Center in Kigali, though, I realized I had other lessons to learn. Stories of victims of the genocide told of dreams and lives cut short, including that of a 12-year-old girl whose life ambition was to be a doctor. This was a reality she would never see, and one I had callously rejected.

Later, as I visited tuberculosis clinics, entire villages affected by HIV, and orphanages filled with children of the genocide, I quickly realized that I was being equipped with knowledge and skills that were not to be wasted. I left Rwanda with a renewed heart for medical service. I went to teach neonatology and professional skills with the Canadian Neonatal Network in Shanghai. I also participated in a pediatrics conference organized by my parents in Suzhou, China – a humbling experience, as I struggled with language difficulties and feelings that my father might overshadow my identity as a newly qualified pediatrician. Despite my frustrations, I was encouraged to have patience, as everything would happen in its own time.

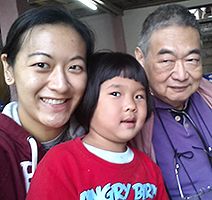

Three years passed. I completed my residency at the University of Saskatchewan and a fellowship in pediatric rheumatology at UBC when my parents invited me to join them for another trip, this time to Thailand and Myanmar. I was by far the most junior member of a 10-person team, but quickly felt acknowledged as an integral part of the team, and an equal among many senior health care professionals and seasoned workers.

While in Myanmar, one of them urged me to make medical service a regular part of my practice. He said my youth, skills, and ability would not be with me forever, so I should use the gifts I was given while I was able. To make his point, he explained that his wife, an occupational therapist who shared his commitment to medical service, could not come on this trip because she was now struggling with fibromyalgia.

In the end, however, it was the story of another 12-year-old girl that put things in perspective for me.

Mae Ai had travelled from the Laotian border, 11 kilometres away on rural backroads, to seek help for ankle pain and swelling she had suffered for two years. Our interpreters found her complaints laughable, because she looked so well, but I quickly recognized she had juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and was in need of treatment. At that moment, I was grateful for my training that allowed this girl to have a diagnosis as well as a chance at a better life. My father, on hearing about my patient, further encouraged me, saying it was fortunate for me to have been able to see a patient from my own subspecialty, as I would know exactly what to do. But the way I saw it, Mae Ai was truly the lucky one, and I was simply a messenger.

I had lost sight of my purpose when I became too focused on myself – a common pitfall amongst the busyness of medical school, training and then establishing a practice. Such professional self-involvement can obscure the rewarding and meaningful contributions we can make to the lives of others.

I now seek to embrace, rather than dread, the responsibility that comes with a medical education. My experiences in global health have strengthened my sense of purpose. For this, I see no better way of showing my gratitude than by giving back to the communities I serve – here in B.C., and overseas. Should I ever lose my way again, I know I have to do only this: Follow in my father’s footsteps.

Mercedes Chan is a pediatric rheumatologist at BC Children’s Hospital. She is also enrolled in the Master of Health Professions Education program at Maastricht University, though the Faculty of Medicine’s Centre for Health Education Scholarship.